-

Richard Powers’ cover for the 1960 edition

4.25/5 (Very Good)

Sarban, the pen name of British diplomat and author John William Wall (1910-1989), spins a hypnotic horror in which a soldier, escaping from a Nazi prison camp, awakes in a dystopia a hundred years after Hitler’s victory in WWII [1].

Drawing on a rich English tradition of pastoral novels, The Sound of His Horn (1952) [2], despite its brief length, weaves a disquieting vision of the mechanisms of power and control [3] It’s unusual. It’s terrifying. It’s possessed by a gorgeous turn of phrase. And, in its most ruminative moments, an incisive exploration of the nature of desensitization and the fear that underpins all actions.

I struggled to write this review. I apologize if it is not as analytical or in-depth as my best.

From Oflag XXIX Z to the Schloss

Lieutenant Alan Querdilion returns from WWII transformed from a “gay young man of abounding energy” to an “inactive and wondering creature” (14) — a symptom of the “flatness and fading of the world” England experienced since 1939. His vivacious fiancée, embroiled in a debate over the nature of fox hunting, does not rouse him from his torpor. He can only interject, hinting at the fantastical trauma he experienced, “It’s the terror that’s unspeakable” (7). As the gathering disperses, Alan relays an otherworldly story to the narrator, giving form to the terror that haunts him.

After his ship sunk off Crete in 1941, the Germans imprisoned Querdilion at the prison camp Oflag XXIX Z. He acknowledges “it’s not unknown, of course, for a man in a prisoner-of-war camp to go round the bend” (12). And perhaps the events after his tunneled-escape from the camp are such delusions. Wandering days in the woods, too thirsty and sick with fatigue to eat, Querdilion encounters a distinct section of the woods: “not black, monotonous pine-forest, but a fair greenwood of oak and beach and ash and sweet white-flowering hawthorn” (19). He stumbles down a gentle slow and experiences a searing shock that “jarred along every bone in my body and shattered its way upwards, tearing out of the top of my skull” (20). He awakes in another time, another place.

As he gradually moves from “passive perception to active observation” (21), Querdilion believes that he might be in a private mental home — his two nurses divulge little. But the sounds of WWII cannot be heard. Instead, from the woods that surround his hospital bed a horn sounds. At first, he believes the “sounds were dream-sounds” but they were notes “as lonely in the pitch dark and utterly silent, as one single sail on a wide sea” (27). Soon Querdilion ascertains the truth of his locale — the Schloss of Count Johann von Hackelnberg, the “Reich Master Forester,” who hunts at night (29). The year? The one hundred and second year of the “First German Millenium as fixed by our First Fuerhrer and Immortal Spirit of Germanism, Adolf Hitler” (35).

As the only survivor of the Bohlen rays that surround the area, Querdilion is the prisoner-patient of his doctor, Doktor Wolf von Eichbrunn. Eichbrunn gives into Querdilion’s desire to learn more about his strange prison — he wants to escape. And soon he learns about the nature of the hunt, Johann von Hackelnberg’s disturbing spectacles of brutality, and how the Nazis continue to perpetuate their ideology. “They are cheaper than machines,” the Doctor proclaims when Querdilion enquires about the mute servants that scrub the floors, “the Graf has a prejudice against mechanisation. He concedes a point or two on the apparatus of destruction, but he would rather give me three slaves than one vacuum-cleaner” (38).

Horror awaits. And a meeting with one of the count’s feathered prey.

Final Thoughts

A few historical events that might have inspired Sarban come to mind. Expanding on historical examples of Nazi experiments conducted in concentration camps, Querdilion encounters a world in which new technologies–“mechanically induced conception” and “the Roeder Schwab process for the acceleration of growth” (38)–continue to perpetuate Nazi ideology of the master race. According to the Doctor, the “lumps of undifferentiated Under-Race” are breed across the German Imperium to be slaves 38). And the Reich Master Forester utilizes genetically modified human-cat hybrids as instruments of torture.

Another event that I can’t help but think about is the Mühlviertler Hasenjagd (the Mühlviertel rabbit hunt) (February 2nd, 1945), in which authorities authorized German civilians and local Nazi organizations to hunt down and kill hundreds of Soviet escaped prisoners from a subcamp of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. While I might be grasping at bit, the dehumanization present in the title “rabbit hunt” could have been the entire genesis of the Sarban’s nightmare (the title itself comes from an English hunting song).

I found The Sound of the Horn‘s most effective moments weren’t the gruesome theatricality of Count Johann von Hackelnberg’s hunts or human animal hybrids but rather Querdilion’s quiet thoughts about the nature of desensitization and the fear that underpins all actions. When he returns to the hospital to find supplies for his escape, the nurses that had tended to his wounds “stared” with “eyes so shockingly full of mortal fear that I had appeared to her by moonlight draped in the earthy cerements of the grave I do not think I could have affected her more” (72). This is a world where the Count’s control is absolute. A moment of empathy cannot exist. The henchmen of the Count “are monomaniacs, and the most inhuman thing about them is the way they fail completely to see that you are a human being” (79).

Querdilion also finds himself unable to grasp the nature of what he sees. Only when he watches Kit, the feathered prey of the count who attempts to assist him, does he realize the “maniacal consistence in every detail of the life Hans von Hackelnberg ordained of his slaves that there was no escaping the trammels of his one mad theme” (85). He marvels at how she could survive at all with an “unwarped spirt” and admires her “courage and cool defiance” (80).

Her humanity and love in the face of Hell, hammers home the bleak horror of it all.

Notes

[1] Is it alternate history? Fantasy? Horror? Or some combination of the three? I’m not going to spend more than this note referencing the debate about what genre Sarban’s work falls into. Most, including the intro by Kingsley Amis in the 1960 Ballantine edition, seems to think the novel classifies as fantasy. In 1988, David Pringle placed the The Sound of His Horn (1952) on his list of the 100 best fantasy novels. I tend not to be personally invested in debates over genre and cast my net widely.

[2] As I am not versed in English precursors to Sarban’s literary style, check out the literary genealogy Nick at Existential Ennui lays out here. He links the novel to the works of Geoffrey Household.

[3] I recently purchased Gavriel D. Rosenfeld’s The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism (2005) to better understand the impact of alternate accounts like this one.

-

Uncredited cover for the 2018 edition

-

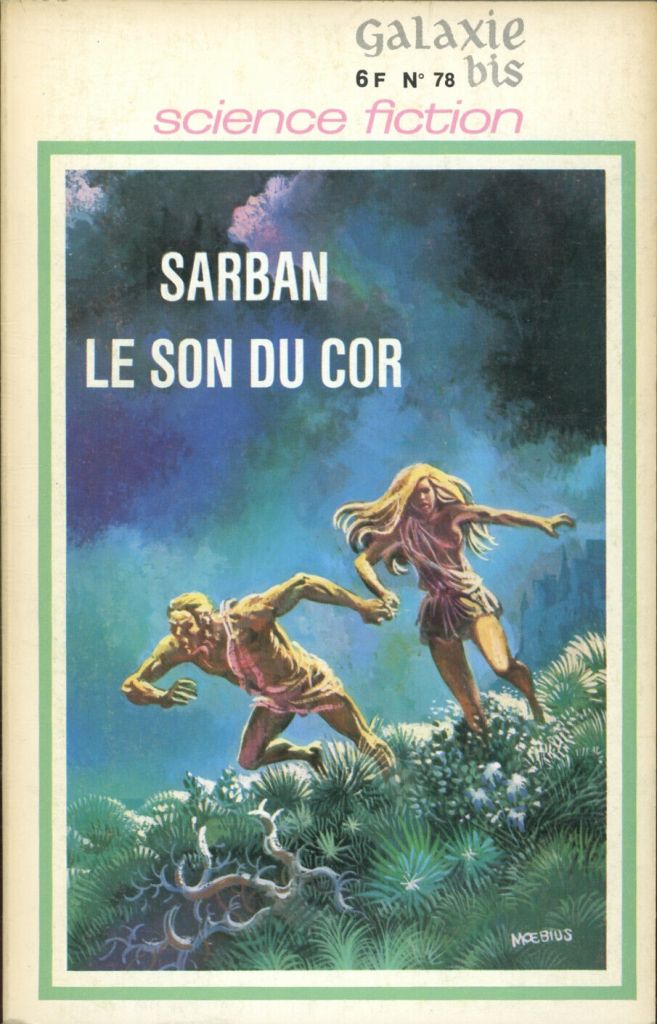

Moebius’ cover for the 1970 French edition

-

Uncredited cover for the 1971 edition

-

Uncredited cover for the 1969 edition

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX