After watching the first episode of the new Fallout (2024) adaptation a few nights ago (I like it!), I impulsively decided to push aside all my unfinished reviews and write about two more nuclear gloom tales. I selected two by Robert Bloch (1917-1994), best known as the author of Psycho (1959), whose SF output I’ve only recently started to explore. Both stories are slick satires that use the nuclear scenario to poke holes in the stories we weave about American exceptionalism and progress.

Let’s get to the nightmares!

-

Richard Powers’ cover for Star, ed. Frederik Pohl (1958)

3.25/5 (Above Average)

“Daybroke” first appeared in the only issue of Star, ed. Frederik Pohl (1958). You can read it online here.

Robert Bloch’s “Daybroke” attempts to convey an encyclopedic glimpse of post-apocalyptic destruction in order to comment on the society allowed the usage of a nuclear weapon. Despite its appealing structure, the story lacks the prose necessary to sear and burn–the last sentence, well, that you’ll remember.

Vignettes of Cataclysmic Ironies

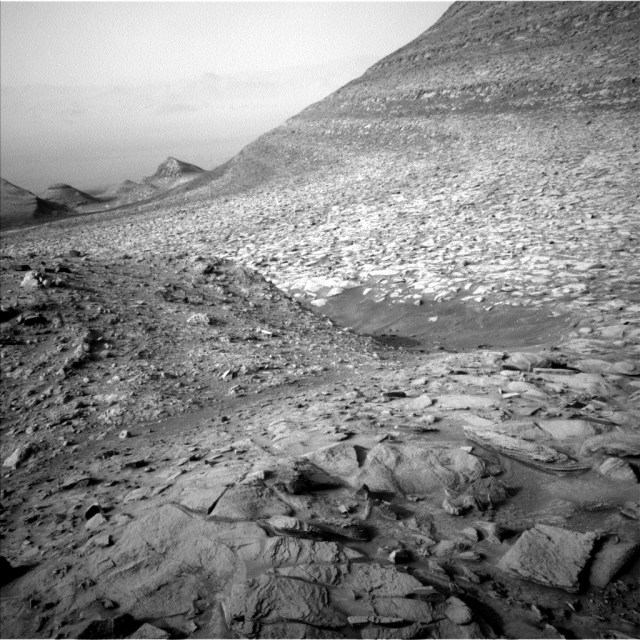

A nameless figure, “godlike and inscrutable” within his mountain-top “vaulted sanctuary,” journeys in a radiation protection suit into the devastated city below (68). He had been one of the few to take the warnings seriously, and to detach himself from the fantasy of normalcy in order to build his survivalist sanctuary. Snark pervades the bleak proceedings. The nuclear explosion interrupts an advertisement for the world’s most popular laxative (69). The same laxative fills the shelves of the nameless figure’s shelter. And so the figure wanders though the suburbs into the city center. He watches the few survivors scuttle to-and-fro before the radiation sickness ends their final movements. Eventually he comes across a government building, and the true irony hits.

Inspired by the John Hersey’s bestseller Hiroshima (1946) or less likely Philip Morrison’s “If the Bomb Got out of Hand” in One World or None (1946), a large portion of Robert Bloch’s story is comprised of grim vignettes of nuclear horror on our narrator’s journey.1 Unlike Hersey, Bloch deploys a series of ironic dichotomies caused by the blast that serve to ridicule and lambast the society that allowed for a nuclear future. Often what the figure sees are personified material objects, the wrecked “Cadillac-corpses, the cadavers of Chevrolets, the bodies of Buicks” (70), reflecting society’s obsession with materialism.

Once past the “miscellaneous debris of Exurbia” (71), our wanderer observes a scientist who died while observing a single cell, representing science’s refusal to tackle the large ramifications of dangerous discoveries (74). In another instance, a broker dies somehow surrounded, like a mummy, with the ticker tape of his trade: man so obsessed with the pursuit of money that he failed to notice the end (75). A once-immaculate broadcasting soundstage inundated with the products that sponsored it: the capitalist truth beneath the veneer of free speech (75). Often the cataclysmic ironies come off as simply cruel rather than revealing. An artist’s body explodes in the blast and becomes the paint on his canvas (74)… A beautiful woman reliving herself in the street, dies positioned as if in a sexual act with a pigeon “nestled in her golden pelvis” (74).

The culminative effect is one of encyclopedic didacticism, the parts of the lesson synchronize into the final punchy, and horrifying, reveal. A deluded world creates the ultimate delusion. Somewhat recommended.

That said, I thoroughly enjoy Richard Powers’ interior art! (below).

-

Richard Powers’ interior art in Star, ed. Frederik Pohl (1958)

-

Chesley Bonestell’s cover for the 1st edition

3.5/5 (Good)

“The Head” first appeared in The Ides of Tomorrow: Original Science Fiction Tales of Horror, ed. Terry Carr (1976). If you have an Internet Archive account, you can read it online here.

The Savage Corridors

The ten-year-old Jon spends his days fighting other gangs in the corridors beneath the blasted post-apocalyptic surface. He yearns to kill his father Grope. One day, as it was “raining too hard for him to go out and kill anybody” (177), he wanders amongst the lower levels of the human warren to the place where the walls were “hard and shiny” with a “buzz noise” from within (179). Inside this unground installation the eponymous real human head resides in its container, turn off, waiting for someone to find it. Jon flips it on.

An artifact of the pre-nuclear war era conceived as the ultimate way to teach future generations about lost technology, the human head attempts to keep Jon interested. It’s “hell when Jon turned him off and left him alone in the dark” (184). But there’s a problem. Jon only knows violence. He wants the head to tell him abd “big kills” and how to “make bom [sic]” (185). The head decides to swing wildly at the narrative that must still resonate amongst the denizens of the decayed Earth–he channels the most powerful stories of the Judea-Christian heritage he can conjure. He takes on the voice of God. Will it be enough?

The Delusion of the Timeless Story

Biblical paradigms often inform post-apocalyptic science fiction. For example, the Adam and Eve story, with its overt connotations of recreation, remains the most popular.2 Robert Bloch’s story joins Damon Knight and Thomas M. Disch, among others, as authors critical of the value and possibility of re-enacting the Judeo-Christian narratives in a post-apocalyptic future. Jon and his people have changed in ways the pre-explosion survivors, even those designed to teach and form the new generation, cannot grapple with: “God, how could he educate this?” (183).

The value of “The Head” resides in its ruminations on the delusion of the timeless story. The head attempts to create a religious parallel between the present and the Biblical past: “in a way, of course, this new world was the Garden of Eden he talked about–Earth in the day before the fall” (183). But the further his analogy goes, the “racial, political, religious, ideological, sexist strife with its breakdown of communications on every level” standing in for the Tower of Babel and the nuclear war as “the Flood, wiping out the world” (183), the more and more it all sounded like a “fairy tale” (183).

Even the head doubts the value of repeating the biblical stories to Jon to help him understand his place and responsibility in the new world. But when faced with his own oblivion, the head can only repeat the past. But the world has moved on.

If you’re interested in meta-discussions on the role of archetypal narratives in science fiction, then this one might hit the right buttons. Somewhat recommended for everyone else.

Notes

For book reviews consult the INDEX

For cover art posts consult the INDEX

For TV and film reviews consult the INDEX