Group Read 72: The Best Science Fiction Stories of 1957

“The Queer Ones” by Leigh Brackett #02 of 20 (Read)

Ever wonder why science fiction imprinted on you as a child? Why does the genre appeal so strongly to some people? What’s its subconscious attraction?

Psychoanalyzing 1950s science fiction reveals a deep-rooted desire to contact aliens. UFOs became a mania in that decade, which spilled over into the 1960s. UFO crazies seemed to have disappeared after that. But they’re back today. I do believe that humanity suffers from cosmic loneliness. Or is it something else?

“The Queer Ones” by Leigh Brackett speaks to both xenophobia and loneliness. I’m not going to give spoilers right away, but I recommend you follow the link above and read the story. It offers bit of a mystery, so I don’t want to spoil your reading fun, but I want to have my say eventually. However, “The Queer Ones” fits the mold so well for this kind of 1950s science fiction story, that it might not be much of a mystery for aficionados.

My first reaction to reading “The Queer Ones” was to feel it was a mirror image of Zenna Henderson’s People stories. But instead of finding gentle aliens out in the backwaters of rural American, we encounter thugs from the stars. I’m reminded of Heinlein’s Have Space Suit-Will Travel. Henderson’s aliens are a version of the Mother Thing, while Brackett’s aliens act like Wormface, but they look human. They even coop human lowlifes.

Leigh Brackett takes on the tone of Clifford Simak in “The Queer Ones,” and it’s hugely different from her planetary romances. She can’t seem to resist herself though because romance does sneak in towards the end.

Hank Temple is the owner/editor of a small town, six-page newspaper. Doc Callender contacts Hank about a curious child, Billy Tate. X-rays and bloodwork show this kid to be strangely different. If fact, the doctor had been called in because Bily had been beaten up by other kids for being different. He looked human, but Billy was slight, redheaded, and a tiny bit odd.

As it turns out, Sally Tate is a young country girl who got put in the family way by a fast-talking stranger. Her child, Billy, grew up to become a kid that Sally’s hill country clan intensely disliked. The Doc calls Hank to see if he wants to drive out into the middle of nowhere to meet this backwoods family. That’s when the mystery starts. Hank and Doc’s first theory was Billy was a mutant.

Mutants are another popular theme of 1950s science fiction. The cause of mutant humans in SF is varied, but two reasons were popular. Radiation from atomic bombs, and the emergence of Homo Superior was the other. This also paralleled our fascination with aliens. Either they were monsters, or advanced beings with godlike powers. Both show up in “The Queer Ones.”

However, the beginning flavor of “The Queer Ones” is much different than the flavor at the end the story. Early on, Brackett taps into the kind of atmosphere we find in Way Station by Clifford Simak. I’d call that theme: Aliens Living Hidden Among Us. Other books like that are A Mirror for Observers by Edgar Pangborn, The Man Who Fell to Earth by Walter Tevis, and as I’ve already mentioned, Pilgrimage: The Book of the People by Zenna Henderson. Superman comics did this too. Henderson essentially steals Superman’s origin story for her People stories. And if you remember, quite a few episodes of The Twilight Zone featured beings from beyond living amongst us.

The plot takes a sinister turn when Doc is killed. Hank realizes their snooping has gotten back to Billy’s father. Then the hospital is burned down with Doc’s evidence. That’s when Hank catches his first alien, a young woman, Vadi, who turns out to be the sister to Billy’s father. That’s when Hank realizes that Billy’s father is not another mutant, but an alien.

Hank is turned on by Vadi. Sally Tate, and all the women of her family had been turned on by Billy’s father, who we eventually learned is an alien called Arnek. Now this is an interesting sub-theme of cosmic loneliness. Leigh Brackett doesn’t go into this, but how can Arnek mate with Sally Tate and produce a child? This has come up in later science fiction stories. A theory to answer that question is panspermia. That theory helps to explain why many of the aliens in Star Trek look human, but it also suggests that God or advanced aliens seeded/populated/colonized the galaxy on purpose. Maybe we weren’t meant to be alone and miss our cousins.

This also suggests that our psychological fear of cosmic aloneness can sometimes overcome our ingrained xenophobia. We want the universe, or at least the galaxy, to be inhabited by beings like us. Even reading stories about aliens gone bad fulfill the need to know were not alone.

Let’s backtrack a minute. Did our hangup of being alone in the universe emerge with UFOs in the late 1940s? I don’t think so. Doesn’t the desire for aliens and angels fulfill the same existential craving? And don’t we have stories of humans and angels falling in love with each other, even having sex. The Bishop’s Wife comes to mind, but then there’s Wings of Desire and City of Angels. Ancient literature is full of aliens if you squint at supernatural beings from a certain angle. Isn’t God a kind of top boss alien? The Bible and other ancient religious work often describe whole species of aliens as part of taxonomy of beings not of this Earth. Sure, the Greek gods weren’t light years away, but they were from on high.

Science fiction doesn’t have that many themes. It tends to explore the same ones over and over, and if you look at them in the right way, those themes have always been around, even before science and science fiction. Just imagine how deep they go when you think about Neanderthals encountering Homo sapiens? We hate the other, but we loath the idea of being by ourselves in reality.

Stories like “The Queer Ones” appealed to me as a kid, and I don’t think I’m alone. Shouldn’t we ask why? For all our eight billion, most of us are lonely. Even if we have plenty of family and friends to keep us company, don’t we feel that something is still missing? Don’t we have a longing for something greater? And isn’t the reason so many people believe in God is because they want a personal relationship with a higher being? Wouldn’t you want a personal relationship with an alien?

In the end, Sally runs off to the stars with Arnek, leaving Billy behind. Hank takes Billy to raise him but wishes he had a wife to help. Hank doubts he will ever marry because after kissing Vadi once, he longs for her too much to settle for a human companion. That’s very strange, don’t you think? Is Brackett suggesting that we’re missing a higher spiritual connection because aliens are our true soul mates?

I doubt we’ll ever meet aliens on Earth, or visit them on other worlds, but we might not stay alone for much longer. Artificial intelligence is progressing so fast that we might have new digital friends soon. R. Daneel Olivaw might arrive before we return to the Moon. Science fiction always promised us robots too. I wonder if we’ll encounter any in the next eighteen stories from 1957.

——

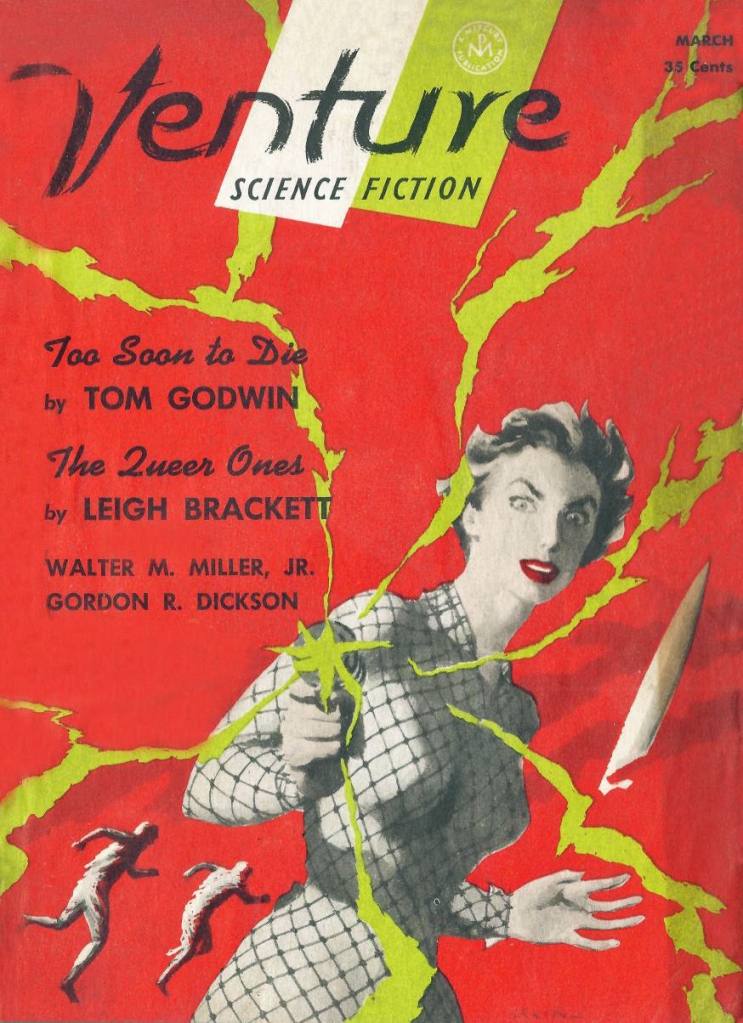

“The Queer Ones” first appeared in the March 1957 issue of Venture Science Fiction. Dave Hook became so entranced by its cover that he researched and wrote “Who is Artist ‘Dick Shelton’.” It’s another fascinating stroll down memory lane if you love old SF magazines and their artists who do their covers and interior illustrations.

James Wallace Harris, 3/13/24